No, You Don't Need a VPN

The last couple of years the VPN industry have flooded the internet with ads for general consumers.

In this post I’ll debunk their claims and tell you the real use cases of a VPN.

What is a VPN?

VPN stands for Virtual Private Network. It is used to route the traffic of one device through another device.

Some use cases can be to connect employees working from home to the office network allowing them access to network resources such as NAS drives. Another use case can be to connect lots of IoT devices across the world to one central network allowing easier remote control and software distribution. Tesla did this on all cars pre-Model 3.

You most likely have one or more devices connected through a VPN today without even knowing it. It might be your car, the electricity meter for your house, your home security system or the work laptop you were given during the pandemic.

Claim #1: Public Wi-Fi

One of the most common use cases brought up by the VPN industry is that public Wi-Fis are inherently insecure and a commercial VPN protects you from “hackers” on the WLAN.

While it is absolutely possible for someone to spy on traffic on an unsecured Wi-Fi, the actual usefulness of the gathered data is questionable.

The fact is that most websites nowadays support Secure Hyper Text Transfer Protocol, or HTTPS for short. HTTPS establishes an encrypted connection between your web browser and the website you’re visiting, and according to Google’s latest report 95% of all web traffic uses HTTPS. From my experience the few websites not supporting HTTPS are commonly unmaintained websites without any sensitive data.

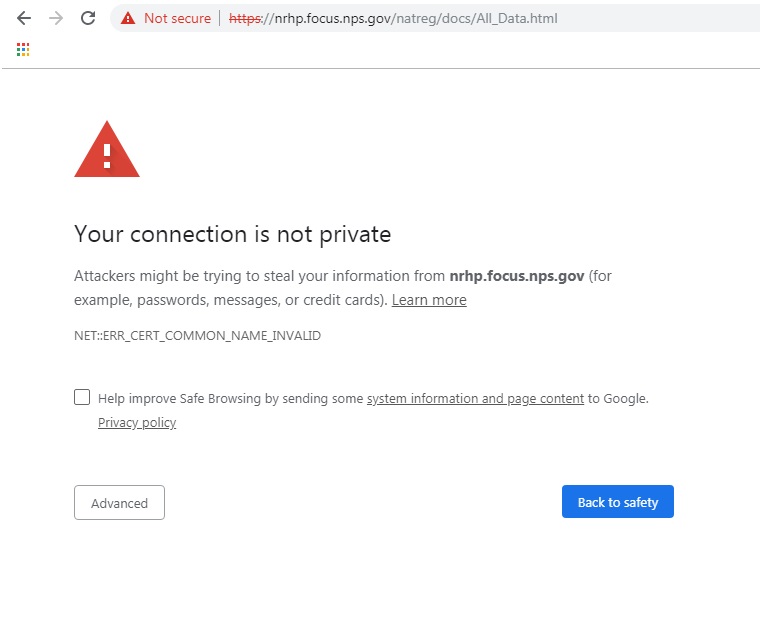

You’ll even see a warning in your browser telling you the website connection is insecure:

But let’s say someone decided to spend the time and effort to capture your web traffic on the public Wi-Fi, what would they see? They would most likely see which website you’re trying to visit. The rest would be encrypted data that is worthless to them. They wouldn’t be able to steal your passwords. They can’t redirect you to a scam site or steal your banking info. All they would see is that you visited the website.

So the prerequisites for them actually stealing anything of value are as follows:

- The Wi-Fi runs a legacy security protocol (WEP/WPA/WPA2) without any kind of password.

- You browse websites that don’t support HTTPS.

- A “hacker” is connected to the same Wi-Fi network as you, and is actively monitoring the web traffic for your sensitive information.

What the VPN tunnel does is encrypt your data between your device and their VPN servers. Past their servers the data is unencrypted. Therefore a better option, in my opinion, is to disable unencrypted traffic completely. Beebom.com have a great guide on how to set your browser to only use HTTPS. I’ve done this since 2019 and have yet to visit a website without HTTPS.

For the more technically savvy people out there, I also recommend you research how to enable DNSSEC validation, DNS over HTTPS/TLS (DoH/DoT) and ECH for your browser. You may also want to increase the minimum supported TLS version to TLSv1.2 along with stronger ciphers. Qualys SLL Labs should be of help.

Claim #2: Use a VPN to view geoblocked content

This claim has been the most frequent claim for some time now. A Netflix series is only available overseas, and you can use a VPN to circumvent the geo-restriction.

This claim is true, but what’s omitted is that you’re breaking the terms of service by circumventing the restriction.

The only reason the content isn’t available in your country is because the service provider isn’t allowed to distribute it in your country. Their contract with the content creators most likely requires them to take measures to ensure only customers located in the allowed countries are able to view the content. By circumventing their restriction you’re opening up yourself to a lawsuit by the service provider, and unlike normal piracy, this time the people going after you have your name, email and credit card.

Do you have the money to fight Netflix or Disney in court? Probably not.

Claim #3: Use a VPN to hide your browsing history

In many countries, ISPs are legally regarded the same way as post offices. And while it may be illegal for the postman to read your letters, it’s often a legal requirement for ISPs to not only read but record your web traffic.

In most western countries the ISP is required to store which sites their customers visit, so that law enforcement can request that data in a criminal investigation.

VPN providers use the fact that our browsing history is monitored to play at our basic desire for privacy.

By using a VPN, your traffic between your computer and the VPN service is encrypted. That means that an ISP only sees that you’re communicating with the VPN, but they can’t see what the communication is about.

The fact that is commonly left out is that the VPN provider now is the one seeing what you’re browsing, and unlike the ISP, which records it for legal reasons, the VPN provider can record it for financial gains.

One of the biggest VPN companies is Kape Technologies. They own CyberGhost VPN, ZenMate VPN, Private Internet Access and ExpressVPN to name a few. Kape Tech was previously an advertising company and it’s not far fetched to speculate that their recent interest in the VPN market is because of the potential revenue in selling user data.

Disclaimer: As long as you’re visiting HTTPS sites, only the fact that you visited the website can be recorded. If you have ECH enabled, the website name is also hidden.

Claim #4: Hide your IP with a VPN

Here’s one of the few marketing points they actually are right about. There is a caveat though.

For those that don’t know, an IP address is like a normal address but for the internet. It let’s your device know where to send website requests, and allows the website server to know where to send the response. However, the system can be abused to send large amounts of data to you, rendering your internet connection unable to handle it all. This is a reason why VPNs are often used for gamers, as the fps gaming community is known for it’s frequent DDoS attacks.

The IP address can also be used to track a user around the internet for advertising purposes. VPN providers often advertise the latter, and the fact that when you use their service, you share an IP address with every other customer rendering tracking infeasible. But just like with claim #1 this issue is becoming something of the past.

With the rapid growth of internet connected devices around the world, we’ve run out of IP addresses to use, and ISPs nowadays assign multiple customers to share one IP. This process is called NAT and is rapidly being adopted by more and more ISPs around the world. Unless you’re actively paying the ISP to have your own IP address you’re most likely sharing one with others. This means that DDoS attacks overloading your own network is mostly a thing of the past for private individuals. What is more likely is that the router responsible for the shared IP will become unresponsive, which will make your internet connection drop for a few seconds before you get assigned a new IP address. This however is the same thing that would happen if you used a VPN.

In conclusion: There’s no real benefit using a VPN to hide your IP address.

Trust in VPNs over ISPs

Many people dislike their ISP. In fact ISPs commonly rank worst in American consumer satisfaction surveys. You will however have a hard time finding an ISP which isn’t bound by local privacy laws. The opposite is true for the VPN market.

In the previous chapter Kape Technologies was mentioned.

Another large company that most people have heard of is NordVPN, owned by nordvpn s.a., a shell corporation in Panama.

The fact is that NordVPN, a company touting its “Nordic ideals of confidence, trust, and innovation” isn’t bound by Nordic privacy laws, European privacy laws or even the lacking American privacy laws.

To me one of the most baffling things about the VPN market is that people actually pay to have their data sent off to unregulated countries.

So before you decide to purchase a NordVPN subscription ask yourself: Do you trust a shell corporation in Panama with your data?

Ping

A crucial yet mostly unspoken thing about VPNs are ping time. Ping time is the time it takes for traffic between your computer to reach the computer you’re trying to communicate with. The ping time is especially crucial for things like Zoom meetings, live streaming and gaming, but other activities can also be affected by the ping time.

Every time you increase the distance between yourself and the target server (website), you increase the time for traffic to arrive (ping). Encrypting each internet packet as the case is when using a VPN, also takes time.

As such, regardless of how close the VPN provider’s servers are located, the ping for you will always be greater than without a VPN, but if you’re connecting to a VPN server in another country the ping will increase drastically. Sometimes to the point where normal internet activities can’t be performed.

Alternatives

For most of the cases listed above modern web browsers provide adequate protection, but let’s say you want to hide your internet traffic from your ISP.

What other options are there to buying a VPN subscription?

The main alternative is The onion router, commonly known as Tor. Tor is a crowd sourced network of computers routing network traffic through multiple computers inside the network before going to the normal Internet. As such, Tor provides greater privacy (through multi-hop routing) whilst being free to use.

A distinction between using the Tor network for visiting normal sites versus visiting “hidden sites” must be made, though. Hidden sites are sites entirely within the Tor network allowing for complete privacy between both the client and website. Simply using Tor as a proxy only protects the client as far as the endpoint, and as such a correlation attack can be made to deanonymize the user. Just like how the FBI correlated the Ubiquiti breach of March 2021 to an ex-employee using SurfShark VPN to.

Posted on by Carlgo11